John to the seven churches in Asia. Grace to you and shalom from the one who is and who was and who is to come and from the seven spirits before his throne and from Jesus Christ the witness, the faithful one, the firstborn from the dead and the ruler of the kings of the earth. Revelation 1:4-5

When most people think of the book of Revelation, they think of a wild book about the future, full of violent visions and fantastic creatures. At most that view is incomplete—it is about much more. And the reality is much saner.

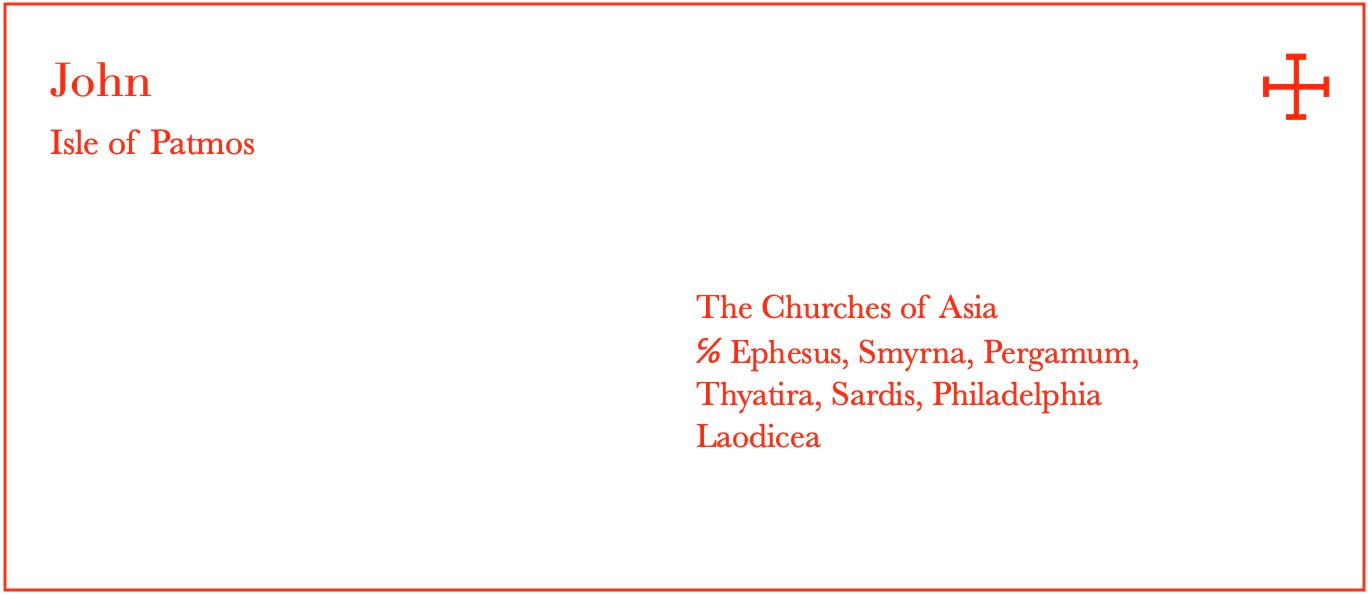

Revelation at its fundamental level is a letter, a complex letter to be sure, but a letter.

In Plain Sight is a subscriber supported publication. If you appreciate the content and insights of this Substack, please consider a paid subscription. Subscribers receive additional material at the end of most posts with more subscriber only material to come.

Revelation as a letter

This letter was written by a living person, John, to specific churches in the Roman province of Asia (modern day western Turkey).

As such, Revelation is a piece of communication from an individual to a group, similar to any letter of Paul or Peter or James or Jude or the other letters of John.

The main differences are the deferred letter opening (not the first verse but the fourth) and the unusual body of the letter (a combination of prophetic speech and apocalyptic visions).

Nonetheless, by definition an actual letter for others (which Revelation is) is assumed to have understandable information to the recipients at that time.

When John wrote the letter of Revelation he assumed his readers would have some clue as to the meaning of the content.

This fact flies in the face of purely futurist views of Revelation which argue that neither John nor his readers understood the letter—that only those in the future with the unfolding historical events at hand would be able to make sense of its contents (and of course history is littered with failed attempts to read current events as fulfilling Revelation, including the last fifty years).

The Evidence of a Letter

First, John has a traditional letter opening.

In Rev 1:4, we read “John to the seven churches in Asia, grace to you and peace from …” This sounds like any Christian letter in the New Testament. He goes on in the manner of Paul to name God, but in full Trinitarian form (Father, Spirit, Son).

Second, in Rev 1:11 in the midst of his first vision, John hears a command: “what you see write in a book and send it to the seven churches, to Ephesus and to Smyrna and to Pergamum and to Thyatira and to Sardis and to Philadelphia and to Laodicea.”

Revelation is a piece of correspondence to be “sent.”

The content of the letter of Revelation is the visions, but real people will be listening to these visions being read (Rev 1:3).

Third, in Rev 2 and 3, we read specific communications to each church tailored to their own historical circumstance. That the communications are prophetic speech from Jesus via John does not change this basic fact.

Fourth, throughout Revelation, John interjects warnings and assurance to his real readers (see Rev 13:9-10, 18; 14:12; 16:15), once again examples of prophetic speech of warning or exhortation.

Finally, in Rev 22, John names himself again as the seer of the visions and ends with a traditional letter closing: “The grace of the Lord Jesus be with all.”

Despite the prophetic and visionary character of Revelation and the need to interpret this content, we must always ground our interpretation in the knowledge that Revelation was an actual letter to actual people living in the actual first century.

The Recipients of the Letter

The typical answer to the question “who are the recipients of the Letter of Revelation?” would be “the seven churches,” and that is true.

The seven churches are particular recipients of Revelation. John saw his visions on Patmos, organized and recorded them, and sent them with specific prophetic messages to the churches of seven larger cities in Roman Asia.

This much is evident. In the months ahead, I will have plenty to say about the seven churches of Asia and the specific messages sent to them.

But a closer look at the first three verses reveals a much broader audience, but one that is still limited.

The first verse indicates this audience: “The revelation of Jesus Christ which God gave to him to show his slaves what is about to happen.”

No English translations have “slaves,” but that is indeed the primary equivalent of the Gr. douloi, and we at least must take that intent seriously, no matter how uncomfortable the idea may seem today.

There are multiple words for “servant” in the Greek language of the first century: therapon, uperetes, diakonos, and leitourgos are the ones found in the New Testament.

But John uses the term for slave.

In Revelation itself, this meaning of slave is evident because three times in Rev 6:15, 13:16, and 19:18, John contrasts slave (Gr. doulos) and free (Gr. eleytheros).

John calls himself and the other followers of Jesus, “slaves.”

This idea is also found with Paul, James, Peter, and Jude; they all refer to themselves as a slave rather than servant.

Why? Because Jesus bought them and owns them (and us).

Bought and Paid for

The enormity of this realization can be overwhelming: I do not own myself, but Jesus owns me. Just a few verses later in Rev 1:4, John writes that Jesus “freed us from our sins by his blood.”

But he frees us from our sins by buying us.

In Rev 5 this reality is clearly communicated in the hymn of praise to the Lamb: “Worthy are you to receive the scroll and to open its seals, because your were murdered and you purchased for God by your blood from every tribe and tongue and people and nation.”

Some readers of English translation might object that the word is “redeemed,” not “bought” or “purchased.”

But the Greek verb is agorazō. In the rest of the NT, the translations regularly translate the term as “buy” because it is the normal term for purchasing some item in the marketplace (think “the Roman agora”).

John is no different in his usage, both in his Gospel and in Revelation. The term agorazō is used clearly in this way in Rev 3:18, 13:17, and 18:11.

This observation about buying us leads to an explanation of the scene in Revelation 7, the sealing of the people of God. Revelation 7:3 states, “Do not harm the earth or the sea or the trees until we have sealed the slaves of God on their foreheads.”

This seal on the forehead is the seal of ownership.

These people were bought by the blood of Jesus and now have a seal that God owns them.

Revelation 14:3–4 describes these people as “bought from the earth,” and “bought from humans.”

Later in Rev 19:2, we see that God is mindful of his slaves: By judging the great prostitute, God “has avenged the blood of his slaves from her hand.”

What is their end?

The slaves of God are enjoined in 19:4 to “Praise our God!” Finally in the new Jerusalem, the slaves of God and the Lamb “will render service in worship” (Gr. latreysousin) to him.

Indeed, we can begin that act of praise today because he has bought us by his blood and we belong to him.

The letter of Revelation is sent to the seven churches of Asia, but those churches are part of the larger body of the church whose members are all slaves of Jesus Christ.

Observations on the Greek Text of Revelation

Rev 1:4 Ἰωάννης ταῖς ἑπτὰ ἐκκλησίαις ταῖς ἐν τῇ Ἀσίᾳ· χάρις ὑμῖν καὶ εἰρήνη ἀπὸ ὁ ὢν καὶ ὁ ἦν καὶ ὁ ἐρχόμενος καὶ ἀπὸ τῶν ἑπτὰ πνευμάτων ἃ ἐνώπιον τοῦ θρόνου αὐτοῦ 5 καὶ ἀπὸ Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ, ὁ μάρτυς, ὁ πιστός, ὁ πρωτότοκος τῶν νεκρῶν καὶ ὁ ἄρχων τῶν βασιλέων τῆς γῆς.

A standard letter opening in the Greco-roman world (compare with 1 Thessalonians, Philippians, and other NT letters):

Author in the nominative case: Ἰωάννης

Recipients in the dative case: ταῖς ἑπτὰ ἐκκλησίαις ταῖς ἐν τῇ Ἀσίᾳ

A greeting and peace wish: χάρις ὑμῖν καὶ εἰρήνη

The grammar of the Trinitarian formula is crazy!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to In Plain Sight to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.